The page shown in Fig. 1 is found in a manuscript book made sometime between AD 1164 and 1177 in the academic environs of Paris, the primary European hub for the bespoke, commercial book trade in this period. It is part of a copy of a very successful text from the milieu of the Paris ‘schools’, the proto-university of Paris, a commentary on the Psalms by Peter Lombard. Peter was made Bishop of Paris just before his death in 1160 but had spent much of his career as head of the school at the cathedral of Notre Dame. Although the Psalms commentary was widely circulated, this particular copy has a series of additions to the basic model that make it a scholar’s delight.

The book is 44cm tall by 31cm wide (about 18×12 inches). It has 184 folios or leaves, each with a recto (front) and verso (back) page. Most copies of this text, without the various additions seen here, would have been rather smaller, but it is not unusual for medieval books to be this big. The folios would originally have been slightly larger, but they have been trimmed by successive binders; the original medieval binding has been lost or removed. This volume holds only the first half of the Psalms commentary (up to Ps. 74); the second half is held in Oxford at the Bodleian Library. The division into two was merely a question of practicality: having the whole text in one volume would have made it unwieldy to use and compromised the medieval binding.

The leaves are made of parchment, which was the most common support for writing of this sort. In this case the parchment is probably the prepared skin of a sheep, although parchment made from a variety of other animals has been identified. Paper was known at this time in the medieval West, but it was less durable than parchment (especially in damp conditions), less flexible, and often less good at taking ink, colour, and gilding, or coping with erasure. Parchment was part of a sheep economy, one of the bi-products, like wool or glue, of animals bred for the table. The success of parchment as a medium can be seen in the survival of large numbers of medieval books and documents, often, like this one, in almost as good condition as when they were made.

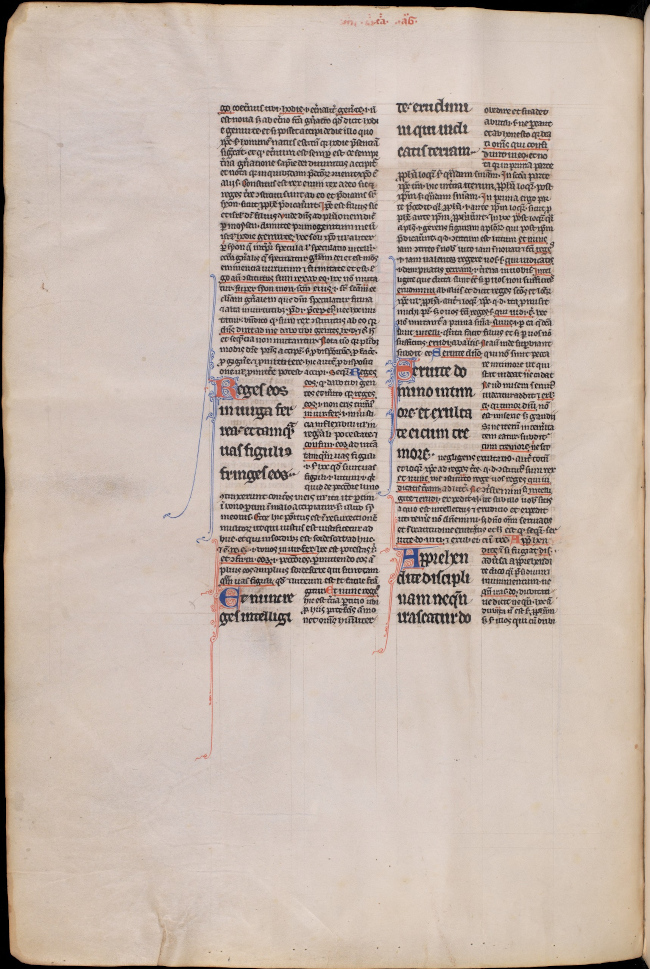

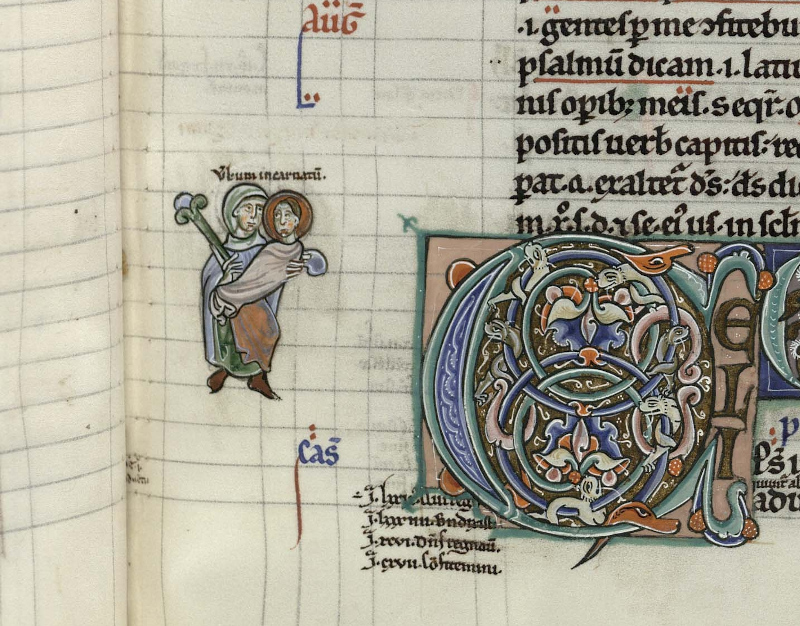

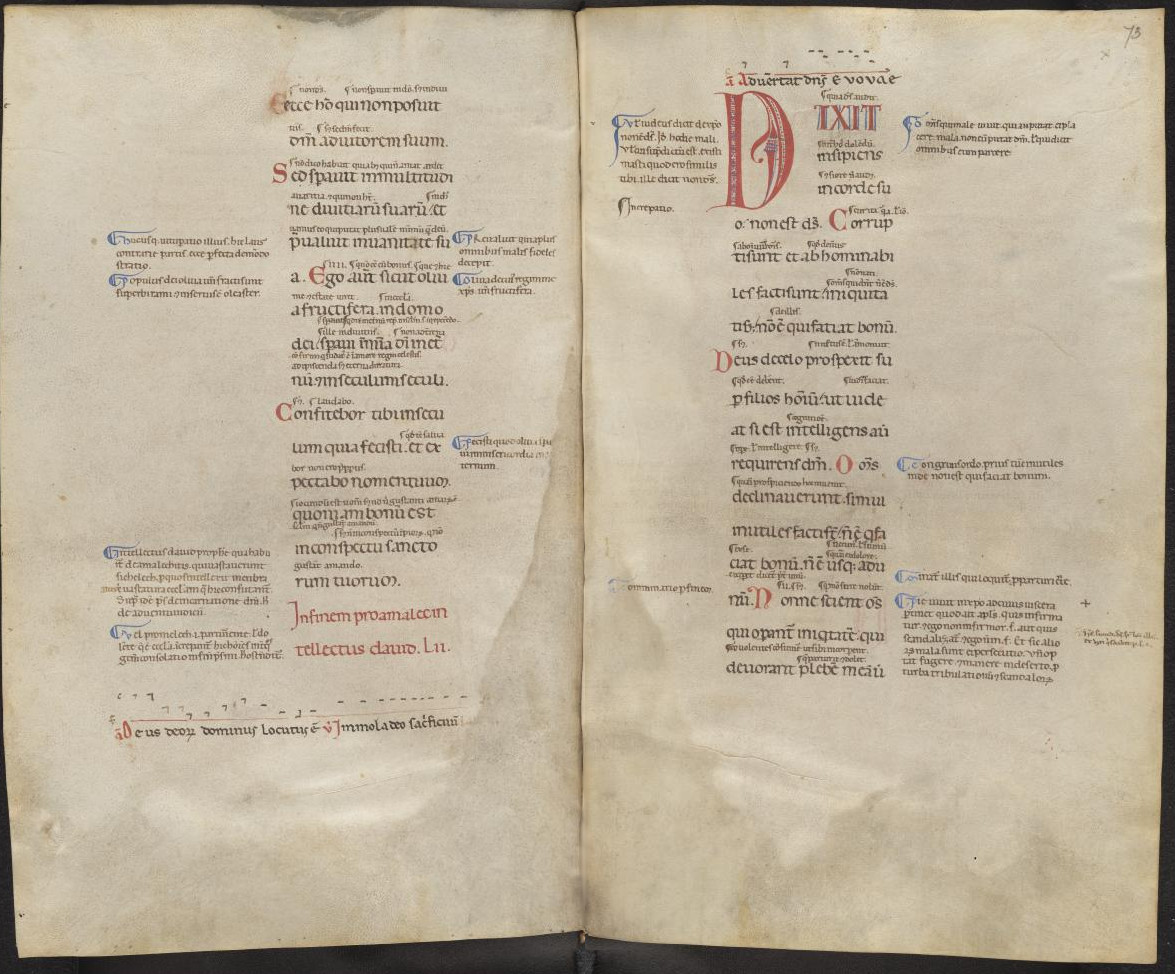

The writing is in the Latin language, which is alphabetic and generally read from left to right, and top to bottom. In this case, however, reading is made more complicated by the fact that the writing is distributed over a running header and a series of columns on the page, eight in all, of which the central two columns are themselves each divided into three sub-columns. This makes a total of twelve columns of writing on each page, plus a header, simultaneously containing seven different texts, not counting occasional marginal notes, comments and instructions, as well as a sprinkling of small drawings which usually have their own short text attached.

Although it had not always been the case, by this period the Latin language was written with word breaks. This manuscript also has a sophisticated system of punctuation, marking paragraphs, sentences, sub-clauses in sentences, and questions. Not all manuscripts have such nuanced punctuation—though most have the basics—partly because it is the easiest thing for scribes to skimp on, miss out, misunderstand, or just get wrong. As is common in scholarly texts, the Latin is written with abbreviations, some of which are standard forms, others merely a sign to show that a word has been shortened in some way, leaving the reader to work out from the context what is meant.

The complex pattern of texts requires a complex system of ruling lines. For this manuscript, this was done by taking a small stack of bifolia and pricking holes at the edges of the page with a tool such as an awl. The holes were then joined with plummet, a lead-alloy precursor of the pencil, to frame the columns and draw lines for the text. In some medieval manuscripts, the lines are drawn with ink or coloured pencil, or simply marked with a blunt edge or drypoint stylus. Frames and lines were bespoke for each text. In this manuscript, the space for the main text block is about 30.5cm by 17cm (about 12×7 inches).

In Paris at this time, each stage of book production had specialist providers. Parchment was made as an offshoot of the butchery trade: the Rue de la Boucherie and Rue de la Tannerie were steps from the river Seine, and the Rue des Parchemeniers and Rue des Écrivains were close by. The different phases of writing and decorating were entrusted to different people, from apprentices who ruled the lines to specialist gilders and illustrators. Everything from the quality of the parchment, to the skill of the scribe, to the amount (if any) of decoration and gilding was variable, determined, of course, by money.

There is a text and commentary, which makes the concept of what is central and what is marginal rather more debatable than when there is only a single text on the page. Medieval books were generally provided with rather generous margins, sometimes so that the reader or owner could add his (or her) own remarks, but also out of a feeling for the balance and spaciousness of the page. Lower margins are generally deeper than upper margins, to give a sense of foundation, and to keep the reader’s hands away from the text. In this case, the text and commentary have been augmented with a series of paratexts and reader-aids, which have eaten into the margin space; but this was nevertheless done with an eye to preserving the balance and harmony of the page.

The growth of the secular production of books came out of a particular academic milieu. During the twelfth century, in Christian western Europe, the focus of higher learning shifted from monasteries to secular schools. Particular places or areas developed specialities—medicine, for instance, was taught in central and southern Italy and southern France, and law in northern Italy, especially in Bologna. Theology and biblical studies, and higher studies in the liberal arts, were the specialism of Paris and the northern French schools. Alongside this shift in teaching and learning came a shift in where and how the books needed for such education, were made, with commercial producers (called stationarii or librarii in Latin) growing in importance over monastic book making. Paris (and its environs) became a hub for innovation in the book trade.

This was especially true for biblical texts with commentary. The beginning of the century saw the start of a project to comment on the whole Bible, laid out in a particular format, with a complete biblical text surrounded by short comments or glosses, mostly drawn from the Latin Fathers of the Church—scholars such as Augustine of Hippo, Pope Gregory the Great, or Ambrose of Milan. It appears to have taken around fifty years for this project to have been completed. Although we think it started in the cathedral school run by Master Anselm at Laon, north of Paris, it was taken to fruition in the cluster of schools in Paris itself, where it was used for teaching by the scholars in the city, and thoroughly revised, probably twice, during the second half of the century. Teaching the Bible via these Glossed books became the standard approach, and copies of the Gloss, as it was known, were in high demand. Thousands of these volumes survive, instantly recognizable by their layout on the page.

The most commonly taught books of the Bible were the Psalms and the Epistles of St Paul, representing the Old Testament and the New, poetry and prose, narrative and preceptual texts. The school at Laon had produced Glossed books on both; but when the centre of teaching moved to Paris, two important masters in the city—Gilbert de la Porrée and Peter Lombard—utilised the Laon Glosses to produce their own commentaries on the two texts, each made according to their own innovative and distinctive page layout. As master of the school at Notre Dame cathedral, Peter Lombard was, in effect, the senior scholar in Paris, and during his lifetime he reserved his commentaries on the Psalms and Epistles for his own use in the classroom. In an academic system based on oral teaching rather than written texts, this was not unusual: before the system of royalties for publication was developed, if a teacher made his materials available for written circulation, he would lose his means of income—how would he attract paying pupils, if they could already read what he had to say? We know the names of many renowned eleventh- and twelfth-century masters for whom almost no written work survives. This was not Peter Lombard’s fate, but he owes a great deal of his fame to the fact that after his death one of his pupils, Herbert of Bosham, oversaw the ‘publication’ of his work in written form. In medieval terms, this meant the production of multiple copies with almost identical contents; but for Peter’s commentary (which became known as the Magna glosatura) it also meant a standardized page layout that made Peter’s text immediately recognizable, and differentiated it from Anselm’s original Gloss (the Parva glosatura) and Gilbert de la Porrée’s version (the Media glosatura), each with their own distinctive mise-en-page.

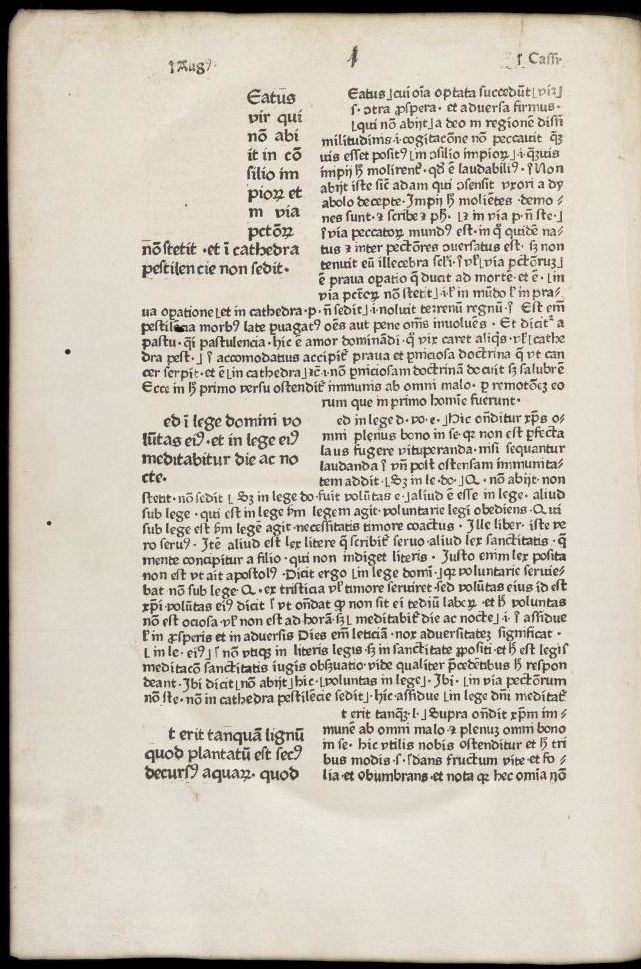

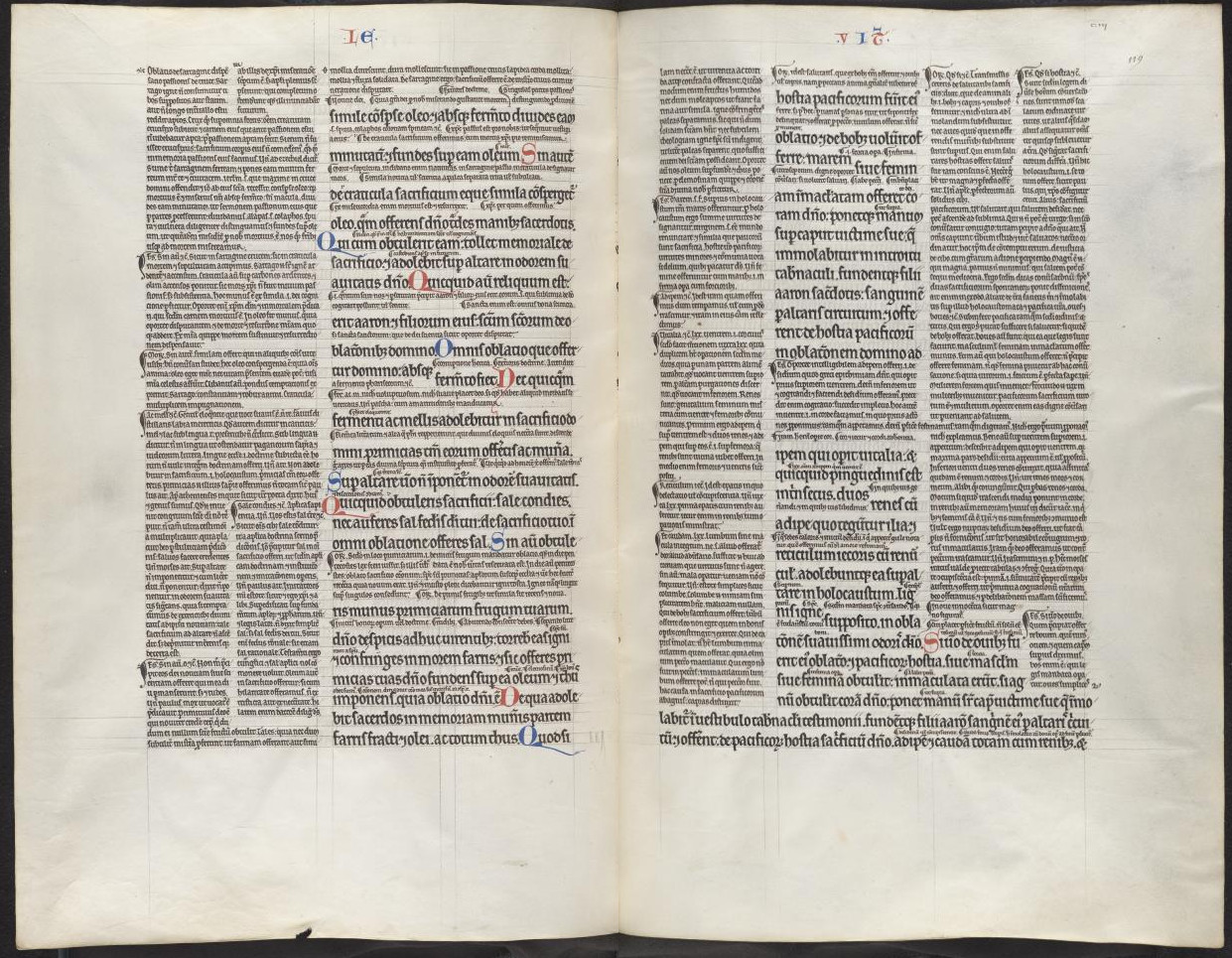

The characteristic layout—known as intercisum or intercut—of Peter’s Magna glosatura combines utility for the reader in navigating the text with simplicity for the scribe in writing it, something that not all glossed texts achieved. The scribe would write a short section of the biblical text in a distinctive script, in a block, left-justified but filling only part of the available column width. The rest of the column was then filled by the commentary on that section of text, with the scribe writing a smaller script, right-justified, and continuing down across the whole width of the column until that the commentary on that section of text was complete. The scribe would then write the next section of biblical text, again left-justified and distinctive, taking up only part of the column width, which would then be filled in with commentary; and so on until the end of the book. In this layout, the whole of the biblical text is present in the manuscript, readily distinguishable from the less-authoritative commentary, and able to be read independently of the commentary, should the reader so desire. And the fact that the scribe could write text followed by commentary, in small sections, rather than having first to write the whole biblical text while estimating what space should be left for the commentary to be added later, as is the case in other Glossed book layouts, made his life much easier, as well as saving on parchment. In these intercisum copies of Peter Lombard’s commentaries on the Psalms and Pauline Epistles, the reader navigates the two simultaneous texts—Bible and commentary—by a hierarchy of script (larger for the Bible, smaller for Lombard’s commentary), and by their position on the page. Dozens of such manuscripts are still in existence (Fig. 2), and the layout was so much associated with Peter Lombard that it continued to be used when the text was printed, beginning in Nuremberg in AD 1475–76 (Fig. 3).

The page we are examining comes from a supercharged—although essentially the same—version of the Magna glosatura, a two-volume copy of Peter’s commentary on the Psalms, which made up a set with a two-volume copy of Peter’s commentary on the Pauline Epistles. Sets of manuscripts—using the same scribes and decorators to produce manuscripts of the same size and style—were surprisingly infrequent in the Middle Ages; however, the prologue and dedication at the beginning of this volume tell us that these books were made under the direction of (and perhaps to some extent actually by) Herbert of Bosham, the scholar we noted earlier as one of Peter Lombard’s pupils. Herbert dedicates the volumes to Archbishop William of Sens, which suggests that Herbert hoped that William would see the excellence of the work and offer him some kind of employment or ecclesiastical preferment.

Archbishop William, however, was not the original dedicatee. Herbert had first caused the books to be made when he was working as a sort of secretary-tutor for a man much better known in the historical record—Thomas Becket, Archbishop of Canterbury and famous victim of gang violence, murdered in his cathedral on 29 December 1170. Becket had been chancellor to the English king, Henry II, and a favoured courtier. When he needed to appoint a new archbishop, Henry turned to his friend, thinking he would be the king’s man; but Becket took his duties as archbishop rather more seriously than Henry had bargained for. Consecrated in June 1162, Becket had fallen out with Henry and left for exile in France by November 1164, not returning to Canterbury until a month before his death. He and his entourage, which included Herbert, spent the first two years of exile at the Cistercian abbey at Pontigny, about 150 km (95 miles) south-east of Paris, a place with a very fine library. Becket was a clever man, if not exactly a biblical scholar, but he began to rectify his ignorance by working every day with Herbert, who describes himself as the archbishop’s ‘master of the sacred page’. To aid his learning, Becket began acquiring and commissioning a number of books—so many that, when they sailed back to England in November 1170, he took with him a biblioteca of 69 volumes, which he presented to the already considerable library of Christ Church, the monastic house at the cathedral. This book was not among them; but we know from the prologue that our copy of Peter Lombard’s Magna glosatura was commissioned by Herbert on Becket’s orders (ita fieri voluit)—though whether to keep for himself, or to present to the bibliophile monks of Canterbury, is not clear. The four-volume set seems to have been unfinished when Becket returned to England, and it is likely that Herbert left it in France to be completed.

Becket’s death, and Herbert’s subsequent attempts to use the books to gain employment by naming both William of Sens and his friend William le Mire, abbot of St Denis, in the various prologues, allow us to date them more closely than we can most medieval manuscripts. Planned in exile at Pontigny in 1164, they were completed (inasmuch as a medieval manuscript can ever be said to be completed) sometime between 1173 and 1177. In the end, Herbert held onto them, only gifting them to Canterbury shortly before his death in 1194. They are listed in Prior Henry of Eastry’s early-fourteenth-century catalogue of the Christ Church library.

Becket, who was described by his contemporary John of Salisbury as ‘the most elegant man of our age’, was not someone to spend a little when he could spend a lot, whether on his clothes and jewellery or on his patronage of the arts. His Magna glosatura reflects a considerable investment—from the cost of the parchment (estimated to have required around 350 sheep), to employing high-quality scribes and artists, working with a multi-coloured palette augmented with gold. It earns its place among these essays, however, not for the undoubted skill and wit of its artists, but because it represents the height of twelfth-century scholarly reader aids. It is a masterclass in ways to navigate a text.

Let us, then, turn to the page itself. Fol. 135v (Fig. 1) shows the beginning of psalm 52, Dixit insipiens in corde suo. non est deus (‘The fool has said in his heart: there is no God’). The psalm verses and commentary are written over two columns in the middle of the page. The scribe has employed the intercisum layout, with commentary surrounding the individual verses (as in the Basel manuscript shown in Fig. 2)—but with an additional riff: instead of only one version of the psalms text, the manuscript has two, presented side-by-side and each present in full. The usual biblical text found in Lombard’s commentaries is the so-called Gallican Latin translation of the Psalter by the third- to fourth-century scholar, Jerome, which he made to a commission from Pope Damasus I from Origen’s version of the Septuagint text—a Greek translation of the Hebrew original. This version, known as the Vulgate, became the most commonly-used Bible of the Latin-speaking Church. But as his ability to translate Hebrew improved, Jerome worked on another translation from the original psalms text, without the Greek intermediary. This version, known as the Hebraican, never gained general circulation, but it was consulted by scholars. It is these two translations of the Psalter that run side-by-side on our page.

Although both versions have the authority of Holy Scripture, they are nevertheless carefully distinguished and arranged hierarchically. The Gallican/Vulgate translation is immediately recognisable as different and important, being positioned towards the centre of each column, on alternate lines, in a script twice as big as any other on the page. The gilded initial that marks the beginning of verse 1 is larger and more elaborate than any of the others. As in many medieval books, the decoration here is not merely ornamental: it serves to help navigate the text. Each of the sections of the psalm (mostly single verses) and the commentary is preceded by a coloured, individually-created initial, but those for the Gallican translation are always slightly larger than those for the Hebraican translation or the commentary. Because of the size of the initial to verse 1, the Hebraican translation has to begin a little below the Gallican; but for the rest of the psalm, the verses of the two sit alongside one another, with the Hebraican always left-justified to the column edge. It is this positioning, rather than the size or line-spacing of the script, or the size of decoration, that marks it out from the commentary, as an alternative scriptural text.

Most of the two main columns is taken up with , which by size of script and decoration is given equal weighting to the Hebraican text. This is not an elevation of Peter’s work, but rather a downplaying of the less popular translation. In the thirteenth-century, most-likely influenced by the interest of the Dominican Order in language and translation, Bibles regularly came to contain both versions of the Psalter, but in the twelfth century this was less common. Here it may stem from Herbert of Bosham’s own scholarly interests as a Christian hebraist: he had worked to learn the language with a sympathetic rabbi, so as to understand both biblical and rabbinic Hebrew texts. But even if the inclusion of the Hebraican translation is Herbert riding his hobby-horse, it is not allowed to detract from the importance of the Vulgate, or leave the reader in any doubt as to which should be given priority.

Peter’s commentary cites the Gallican/Vulgate text, and when it does so, the words of Scripture are underlined in red. In some copies of the commentary the whole of the scriptural text is written in red; but in this manuscript, given everything else on the page, that may have been judged to be over the top. Nonetheless, one further device for textual navigation is present within the main columns, and that is the tituli or superscriptions to the psalms. These are the rather enigmatic biblical rubrics which purport to name the author of the psalm or explain how it is to be read. The tituli are written in alternating red and blue lines of text, unlike anything else on the page, and they mark the end of one psalm and the beginning of the next. Peter interprets them as part of his commentary.

These are the contents of the two main columns. Although there are three major texts, they remain easily distinguishable because of the size and spacing of their scripts, their positioning within the column, and the size and complexity of their decoration. But it is important to realise that the detailed layout is different on every page, simply because the amount of psalm text and commentary varies from verse to verse. No two pages are exactly alike.

The inner and outer margins of the page hold the paratextual material. There are three different texts here, carefully cordoned off from one another by the frame ruling, to ensure they never meet. They are written at half the size of the commentary script, and with two lines to every one line of commentary. The text closest to the main column on either side, written in the same ink as the main text, is a set of cross-references to other psalms of the same type, introduced by an abbreviation for the word supra (earlier in the psalter) or infra (later). (Which psalms were linked by Herbert to which others is a question we shall return to later.) The outermost column on both sides, also written in the ink of the main text, is another set of biblical cross-references, this one to parts of the Bible other than the psalms, along with occasional notes. It is not unusual to find cross-references in commentaries, but rarely in such a systematic manner. The middle column in both margins, however, is unique to Peter Lombard manuscripts—a more sophisticated version of an earlier invention. Peter’s commentary is drawn in the main from the Latin Fathers of the Church, and in particular, for the Psalms, from the works of Augustine of Hippo and Cassiodorus, with occasional contributions by the likes of Ambrose of Milan, Jerome, and Gregory the Great. In most commentary of this period, quotations (or paraphrases) from such authorities would either be unacknowledged (with readers expected to recognise what they are reading), or else only noted in passing, with a phrase such as ‘as Ambrose says’. Peter Lombard, however, seems to have been too careful a scholar to allow such imprecision, and he provides navigational tools which brilliantly combine the main text and the marginal paratext. Whenever there is a quotation, its extent is marked by a red or blue vertical line in the margin, and its author is identified by name, in an abbreviated form: Aug, Amb, Jer, etc. This is unusual enough on its own, but the reference system goes still further, with each author given an individual symbol (a combination of dots or apostrophes, in red), written above their name in the margin, and above the beginning and end of the quotation in the commentary. This middle marginal column is in dialogue with the main text and is so consistently produced that once readers have learned the system, they can ignore the margins and concentrate on the commentary, while still knowing who is speaking: words underlined in red are scriptural; words within the parentheses of red symbols are citations from authorities, each with their own pattern; and everything else is by Peter Lombard.

To make things easier for the eye, the names and vertical lines are written alternately in red and blue. This is at least in part because many of the quotations are from a single author, Augustine, and the alternating colour scheme allows the reader to know that one quotation has ended and another, by the same author, begun. There is one further aid, although it is not used on fol. 135v. For most of the authorities, the text Peter cites is their Psalms commentary. For Augustine, however, there were so many possible works to cite that where the quotation is not from his Ennarationes in Psalmos, the name of the work is also noted.

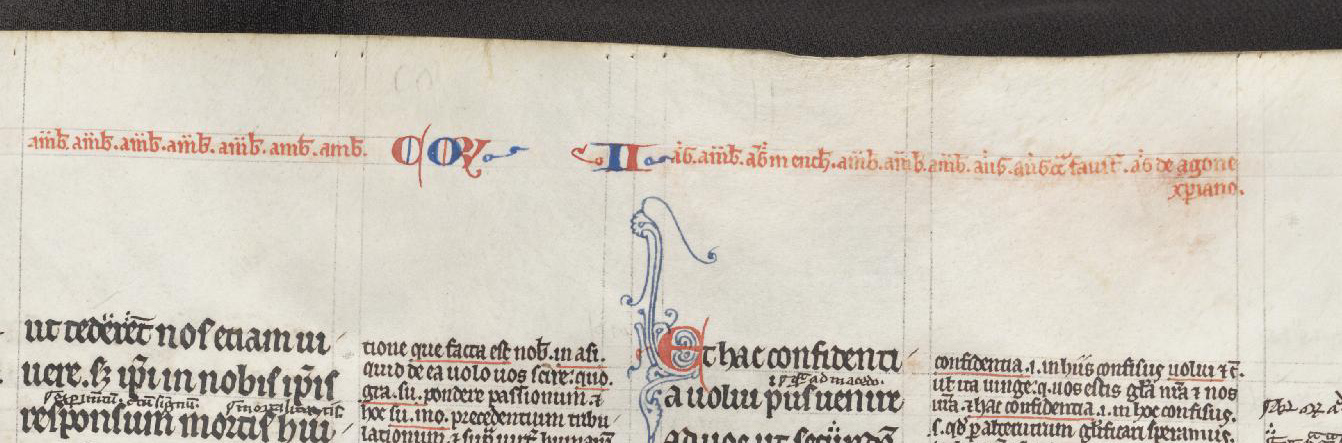

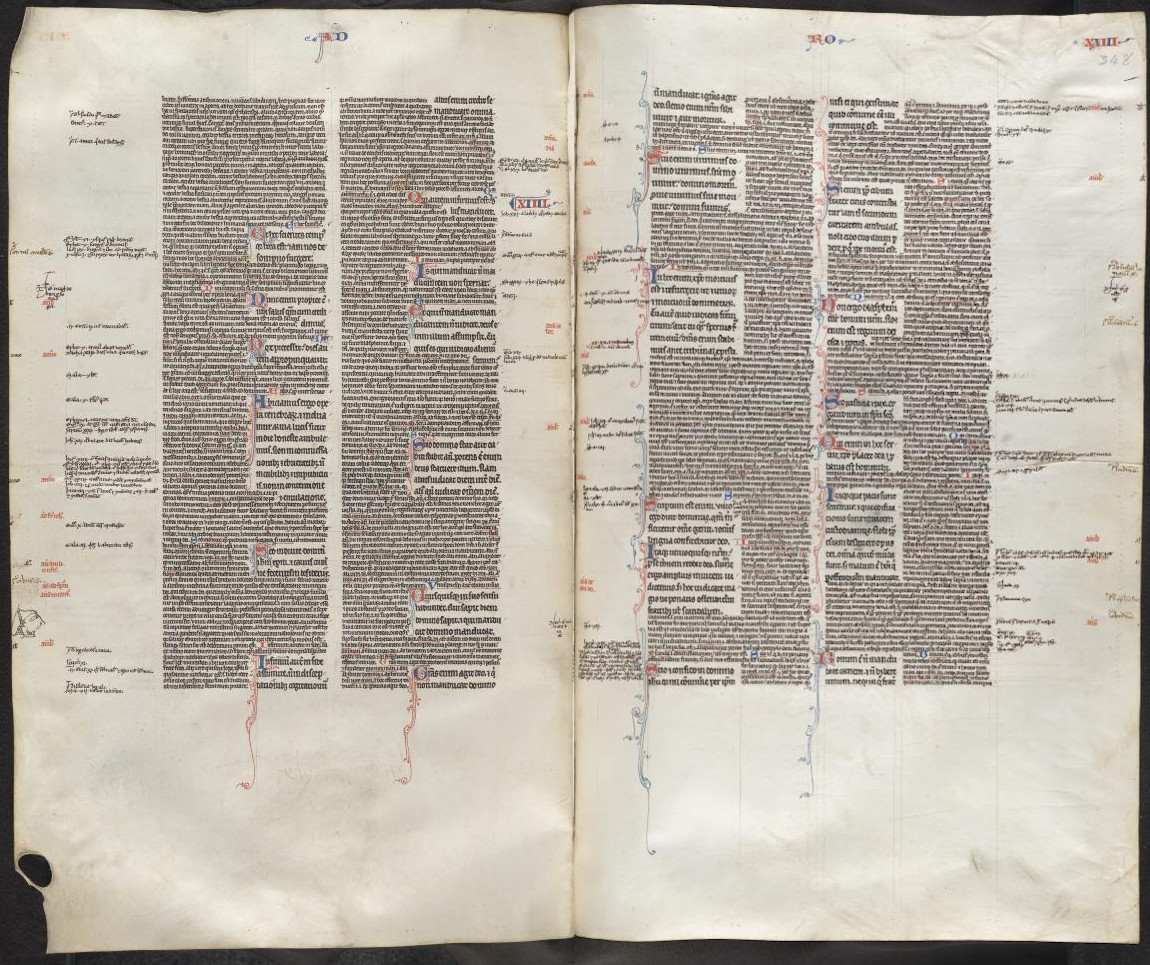

The complexity of this marginal reference system is peculiar to manuscripts of Peter Lombard’s commentaries, but the placement of the references in the lateral margins is usually a feature of his commentary on the Pauline Epistles rather than the Psalms, as they are here. In manuscripts of the Psalms commentary, the names of the cited authorities are generally written in a single line in the upper margin of the page. Given that so many of the quotations are from the same two authors, this can lead to an odd string of repeated names running across the page, as in Fig. 4: aug aug cass aug aug aug… . This arrangement makes it harder for the reader to keep track of who he is reading, particularly in cases where the repeated symbols were (understandably) not copied correctly. It is not clear why the Psalms and Epistles commentaries employed different systems, since positioning the references in the lateral margins is so much clearer.

The final text, also in the upper margin, was added entirely for the purpose of navigation: a header, in alternate red and blue letters, runs across the opening of each pair of pages, giving the psalm number as ps followed by a roman numeral. (Arabic numbers were not generally used in manuscripts until the thirteenth century.) Many psalters of the period would not provide psalm numbers, either as a running header or a simple note in the margin, since readers were expected to know the first words of the psalm (the incipit) and identify it that way. The psalms were often the medium through which medieval children were taught to read Latin, so the incipits would be very familiar.

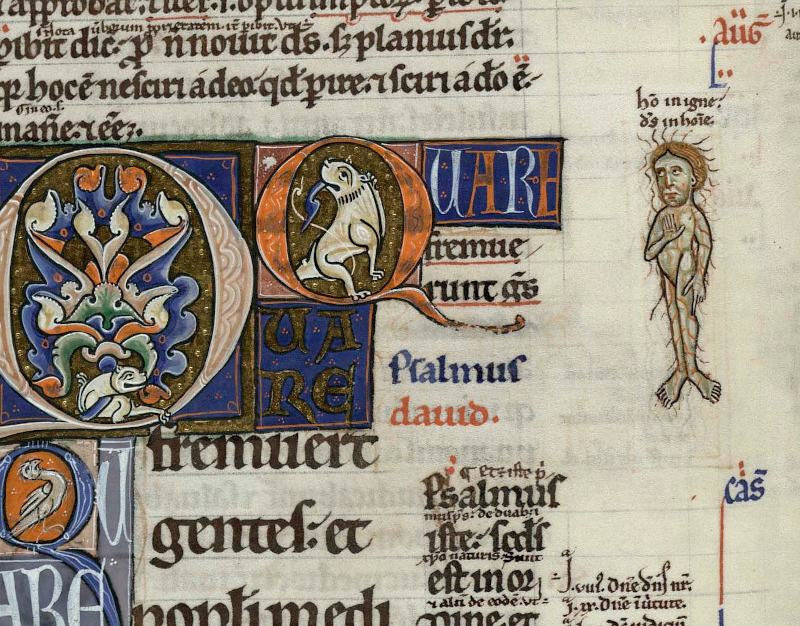

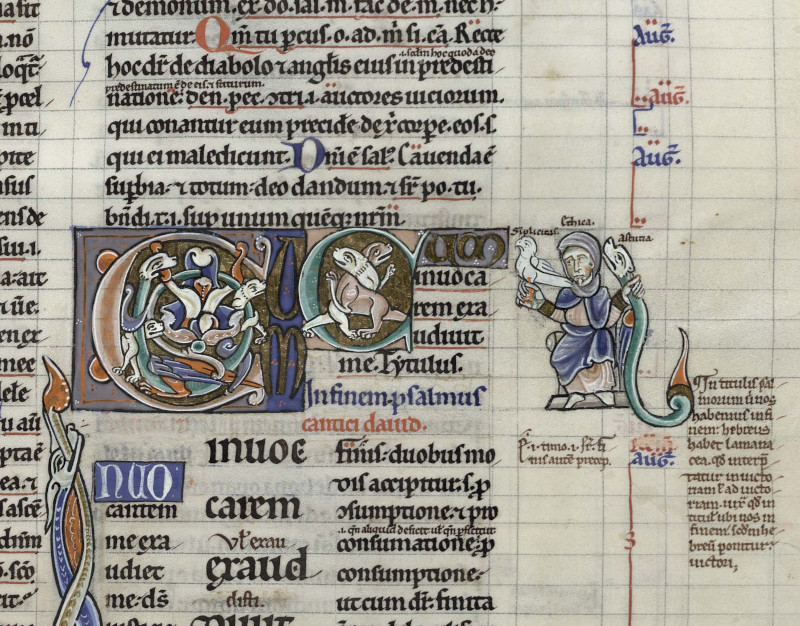

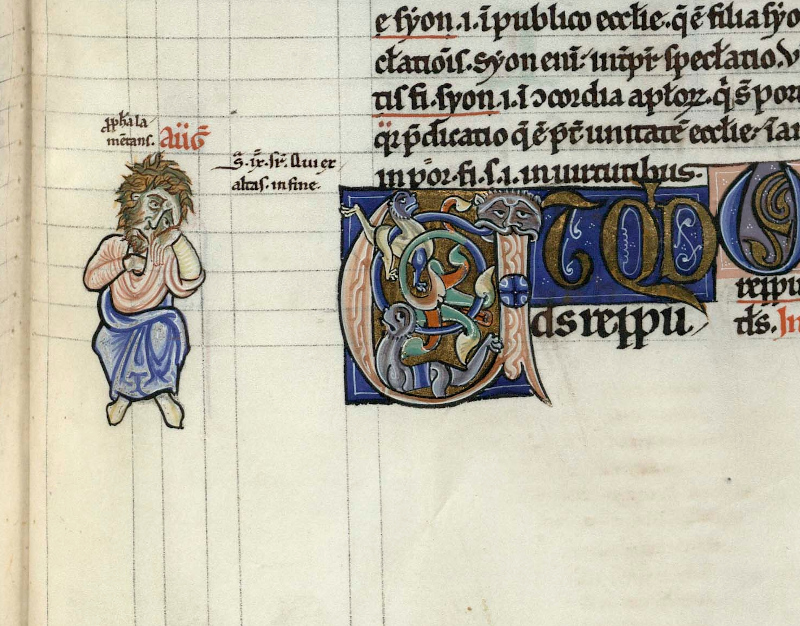

Two further pieces of paratextual material complete the reader aids. The psalter comprises 150 psalms, often divided into groups, according to their themes or meaning. Cassiodorus (the sixth-century writer whose Psalms commentary was commonly cited by later scholars) created a system of twelve categories of psalm and thirteen symbols. Gilbert de la Porrée, whose Psalms commentary appeared just after Peter Lombard’s, used twelve divisions, each with its own identifying symbol. For his edition of the Lombard’s commentary, Herbert has devised his own thematic groupings. Before psalms 1, 50, and 100, he produces a capitula list which assigns each of the following 50 psalms to one of the groups. At the head of each psalm, the others that share its theme are noted in the first cross-reference column. In addition, Herbert has contrived an even more vivid means of noting the connections: some psalms are marked with tiny figures that represent their ‘theological subjects’, as M.R. James’s catalogue notes. These subjects include: the two natures of Christ, designated by a man in flames, with the text Homo in igne. Deus in homine (‘Man in fire. God in man’); the incarnation of Christ, designated by the Virgin and child; psalms of grace and penitence, designated by an old and a young man; and psalms of lamentation, designated by a lamenting prophet (Figs 5–8).

Sadly, no such index figure is present on fol. 135v, and in fact, we are lucky that any of these figures survive, since—as can be seen in the left-hand margin in Fig. 1—the manuscript was attacked by a collector of medieval decoration, probably in the nineteenth century. These collectors—John Ruskin was a famous name among them—cut out illuminated initials and other decoration from manuscripts and kept them in scrap books. This manuscript has lost the majority of its figures to a collector, and the rectangular hole in fol. 135v signals that a figure has been excised from the previous page. However, one figure, in the top right-hand corner of the page, escaped the scissors, and he is typical of others that survive. Around 5cm (2½ inches) high, the figure depicts, by his dress, white hair and beard, an ‘elder’. Tiny script identifies him as Augustinus—Augustine of Hippo. Equipped with a long pointer or arrow, he directs the reader’s attention to a quotation also headed Augustinus—apparently from one of his own works. This, the figure denies: a speech scroll from his mouth reads Non ego—‘not me’! He is correct: the quotation does not come from Augustine’s writings. These two sets of figures—the thematic index and the correction of authorities—may seem whimsical to modern eyes, but they are performing an important scholarly role.

This single page, then, simultaneously holds seven main texts. Seven texts on a single page could be a labyrinth; but the careful use of ruled columns, varying script size, sophisticated punctuation, differential line spacing, position of text within columns, varying size and complexity of decoration, symbols, alternating colours, and horizontal and vertical placement, all mean that each page is a model of managed information. It requires an expert reader, but the elaborate structure is designed to make the text accessible, and all within a page that was also conceived as a visual treat.

Yet for all the complexity of folio 135v, the page also lacks information that a modern reader would expect to find. The most obvious omission is page numbers. Medieval manuscripts today generally do have page or folio numbers, but these are almost always post-medieval additions. Contemporary page numbers were not needed because of the way medieval readers worked with texts. Before the advent of universities, around the beginning of the thirteenth century, readers read from beginning to end. In monasteries, especially, the method of reading was ruminative—a slow and careful process aimed at meditation and spiritual growth. It was only in the thirteenth century that teachers and preachers regularly began to use books in the way we do today—flipping back and forth to find specific sections. The Dominican Order, dedicated to scholarship in order to preach, introduced a series of innovations, such as indexes, in the books they used, although their indexes generally did not refer to a page number but to a section or subsections within the text that was signalled in running headers combined with a division of the page into seven parts (sometimes noted on the page with letters of the alphabet; sometimes simply assumed). Where a modern Bible would have psalm numbers in the margin and numbers to identify each verse, medieval Bibles (and commentaries) at this time do not refer to verse numbers. Indeed, there was no standard division of the biblical text into chapter and verse until early in the thirteenth century. Readers were expected to be experts who could find their way around because they already knew the text.

For Thomas Becket and Herbert of Bosham, exile at Pontigny was not precisely hardship. The abbey had a fine library and was close to the archepiscopal hub of Sens; Paris was not very far away, reachable by boat or barge along the river Yonne. For a group of like-minded colleagues with money to support them, life cannot have been so difficult. Nevertheless, it was still exile, and Becket had grown used to being at the centre of power. He was a pupil who perhaps needed encouragement in his new studies; and Herbert planned and produced a copy of the latest scholarly text, where there was, nevertheless, always something to delight the eye. If a single page seemed confining, the various cross-references could function almost as quizzes or puzzles, to take the mind elsewhere. The tiny index figures were aids to memory, making the links between psalms easier to forge. Memory and sense experience are closely linked, so the variety and interest of each individual page are part of the process of recall. They help a reader navigate the text, and the complexity—and fun—of that journey also helped fix the contents in the mind.

In his prologue, Herbert urges subsequent copyists to copy the whole of his text or not to do it at all. Perhaps he realised just how daunting his extraordinary creation might seem. He got his way, but perhaps not as he had intended: among the many dozens of surviving copies of the Magna glosatura, there are none that display such a complete panoply of paratexts and reader aids. The standard, less elaborate versions of the text were rather different. These usually contain only the Vulgate translation of the Psalms and Epistles (Fig. 9), surrounded by Peter Lombard’s commentary in the intercisum format, along with a truncated version of the marginal references, giving the names of authorities and the extent of the quotations, but without the elaborate Morse code of symbols. Some have biblical cross-references, but not in the same profusion as is present in this manuscript. The earliest types of Glossed Psalter, such as Fig. 10, were made at the beginning of the twelfth century by teachers working in a world of mostly oral and aural tuition as a kind of classroom aide-memoire: they would read out a section of the biblical text, then talk around it, using the marginal glosses as a prompt for what they already knew. But as teaching and learning incorporated more written materials, the model changed. By the last quarter of the century, Glossed biblical books looked like Fig. 11—books made for consultation as reference works, by both teachers and students, not for reading aloud in the classroom. Herbert of Bosham’s manuscripts of Peter Lombard were at the forefront of the new, more complex layout, experimenting with a remarkable range of navigational tools for the expert reader.

Acknowledgement

Images of Bodleian manuscripts are reproduced with the permission of the Bodleian Libraries, Oxford.